Batteries that keep giving: the untold potential of EVs

By Erin Baker, Brand Ambassador

What happens to electric car batteries when they are damaged, faulty, aged or experiencing a loss of performance? This question is increasingly worrying drivers debating whether to make the switch to an EV.

The lack of publicly available, easily digestible answers drives further consumer anxiety around depreciation, reliability, cost and the ultimate environmental impact of driving an electric car. So, the industry—from OEMs to retailers to the media—must get their heads around the facts and communicate the story to consumers in an accessible way.

Discover more content...

Recycling – not a 'silver bullet'

But what are those facts? Well, the first part of the story to get across pertains to the big “saviour” for all shoppers struggling with guilt about their purchases: recycling. Consumers think that if you can recycle it, then that’s responsible buying in a nutshell: buy, use, recycle. No need for further soul-searching.

However, when it comes to electric cars, and their huge, expensive, cutting-edge batteries, the goal is not recycling: the goal is to look after them so well during the first lifespan that they go on for as many years as possible, providing range and power, so recycling is pushed to the last resort.

Recycling batteries right now is very costly, very complex and, in the words of an executive from Fortum, a global leader in recycling batteries, based in Helsinki, “bloody difficult”.

What makes recycling so hard?

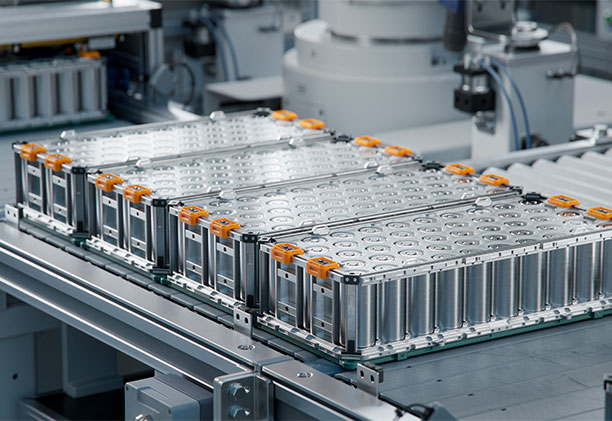

Not only is the disassembly of cells difficult if the OEM’s supplier hasn’t packaged them correctly in the first place (i.e. by welding), but transporting the batteries and their components across borders requires endless paperwork and permits, bespoke to each country, because the components are classed as hazardous waste. You also have to make them safe by discharging them to below a zero state of charge, and they are liable to react during that process if you don’t know what you’re doing. In fact, even storing them is a nightmare because they are essentially a perishable good: they need the right temperature, atmosphere and treatment – you can’t just bung them on a shelf like an Amazon package, so the cost is considerable there, too.

After dismantling them, you have to shred them, during which there are hazardous gases and dust, and the risk of combustion, all of which need to be carefully managed.

At the end of that, you have your black mass, a mixture of anode and cathode materials. It takes “hundreds of millions” to refine the black mass, and you have to consolidate your waste between countries (with their different permits and costs) so they can be refined at one recycling factory.

As for the time scale: Fortum told me it takes nine months just to be compliant to transport the waste… imagine how the paperwork is going to start building up as more of us go electric.

5-10%

Of EV batteries are estimated to have been written off due to accidents of malfunctions.

Repair and remanufacturing could be the solution

Battery recycling plants aren’t receiving the investment they need from the industry up front because car brands don’t know the scope of their requirements yet. In other words, it’s all a bit of a challenge at the recycling end of the journey right now. Promoting a longer, less resource-intensive life cycle for car batteries is the cheaper, more environmentally friendly solution for everyone.

The good news is that it’s as if rare earth metals and other raw materials read our minds and geared themselves up mentally for at least eight years of helping shuttle ions between anode and cathode in a cell. And they do it pretty well, which is why OEMs are happy to whack an eight-year warranty on a battery. You don’t get an eight-year warranty on a petrol engine.

During that period, should things go wrong, a man in a white coat somewhere is ready to deal with it, whether it’s the chief engineer at Omoda (a new Chinese brand in the UK), or the chief engineer at EV Battery Solutions, which supports the OEMs and retailers in managing customer’s battery repairs.

How battery repair works

Mr Omoda white-coat has designed their Battery Management System (BMS)—a sophisticated electronic control module located inside the battery, that controls charging, power, cooling, heating and fault diagnosis—for utmost safety. It’s very similar to the Engine Electronic Control Unit (Engine ECU) in a petrol vehicle. If the vehicle is involved in a severe crash and the battery outer casing is punctured, the BMS will sense that there may be a potential leak and will shut down all high voltage flow inside the battery in two milliseconds, preventing any potential fire risks. Two milliseconds! Clever stuff.

Mr EV Battery Solutions engineer, meanwhile, has created a triage system for poorly batteries, which ranges from your basic A&E arrival check-in to a bed in intensive care, the op and rehab. In other words, if issue is identified, EV Battery Solutions will run a diagnostic check for faulty cells, modules or connections, replace damaged or degraded cells, rebalance the cells for even power distribution, fix any issues around overheating or cooling, repair cables and connectors, update the software and run the battery through a few charges and discharges to check it meets performance standards.

What if it can't be repaired?

Should the battery be well and truly out of luck, EV Battery Solutions doesn't give up: it will do a complete remanufacture, if it feels it’s possible, to restore the battery to where it should have been before it had a tantrum, by taking it apart, replacing cells and components and re-certifying the finished product.

For the consumer, it will do all this having swapped the faulty battery for a working one, so the driver isn’t waiting around while the insurance company forks out for a courtesy car, thus pushing up EV premiums all round.

Now tell me that isn’t better than recycling. Sure, repairing and remanufacturing is complicated and not a very sexy story, but it’s better for the planet, and that’s all that counts.

Let's take charge of the future, together

We’re transforming the in-life battery operations of the world’s leading automotive manufacturers. Get in touch to find out how.